Article first published in electronic form in Volume 31, 2013-2014 This article printed in 2015-2016 includes an additional photograph of Tingley statues at Tingley Beach.

By Zana Alqadi with further research by Ruth Vise

Image caption: New Mexico State Veterans' Home, located at 992 S. Broadway in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. This is the site of the former Carrie Tingley Hospital. (Photo courtesy of AllenS/Wikimedia Commons).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many tuberculosis (TB) patients from the East and Midwest traveled west with hopes they could find life-saving treatment. A dry, hot climate was thought to be the best medicine, and many TB victims settled in the Southwest and lived long, productive lives. Nancy Owen Lewis, writing for the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, said that such health seekers were sometimes called “lungers,” and those with money went to sanatoriums.

The railroad industry advertised the Southwest as a healthful place, and in 1882 in Las Vegas, N. M., the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad opened the Fred Harvey Montezuma Hotel principally for the local therapeutic hot springs. Lewis said that Santa Fe, Silver City and Albuquerque all advertised the curative properties of the clean air and abundant sunshine found in New Mexico.

In 1899, the military opened a hospital in Fort Bayard for tubercular soldiers and by 1912, some 30 sanatoriums had been established, with 30 more to come in the next 10 years. But private ones were expensive: $50 to $100 per month. Tubercular victims without funds often had no place to go, or they found themselves in “tent cities.” The average stay was nine months, but even with good food, fresh air, plentiful sunshine and rest, 25 percent died in the sanatoriums, and 50 percent died within five years, according to Lewis.

Mo Palmer in a 2008 Albuquerque Tribune article wrote that Albuquerque, located in the high desert mountains of New Mexico, had only one TB sanatorium in 1903, and it had a waiting list. But a Presbyterian pastor from Iowa named Hugh A. Cooper, who himself had recovered from TB and decided to stay in New Mexico, convinced the Presbyterian Synod to create a new sanatorium on Central Avenue between today’s downtown and the University of New Mexico, which would be known as the Southwestern Presbyterian Sanatorium, opening in 1908. It later would become Albuquerque’s Presbyterian Hospital.

Image caption: Carrie Tingley was New Mexico's First Lady and helped establish the children's hospital in T or C named for her. (Photo courtesy of Sherry Fletcher, Campo Espinoso, Truth or Consequences, NM)

Image caption: Carrie Tingley was New Mexico's First Lady and helped establish the children's hospital in T or C named for her. (Photo courtesy of Sherry Fletcher, Campo Espinoso, Truth or Consequences, NM)

One woman who came to the Southwest in search of treatment was Carrie Wooster. She was born to a prominent wealthy family on May 20, 1877, in Madison County, Ohio, an only child whose father had died of tuberculosis. At the age of 33, she, too, began to show signs of tuberculosis. In 1910, she and her mother set out for Phoenix, Ariz., in the middle of the desert, in search of a cure. However, she had an acute attack in Albuquerque, and the two left the train for an overnight stay. That overnight stay in New Mexico became a lifetime. She would become one of those many “lungers” who stayed in the Southwest, some becoming leaders whose own illness led them to accomplish a great deal to help others.

Her fiancé, Clyde Tingley, who was still in Bowling Green, Ohio, was a machinist and supervised the Gramm Truck Company. He had been born in an actual log house on a farm near New London, Ohio, in the early 1880s. When he received the news that Carrie was ill, he traveled to Albuquerque to be at her side. Because of the miraculous dry heat that helped Carrie Wooster with tuberculosis, they decided to stay in Albuquerque to seek the therapy that Carrie needed. They were married by the aforementioned Hugh A. Cooper in his pastorate on April 21, 1911.

While Carrie recuperated, her husband Clyde Tingley went to work in the Santa Fe Railway shops, according to Howard Bryan in his book Albuquerque Remembered. Suzanne Stamatov wrote that Tingley entered local politics in 1916 as an alderman for the Second Ward, beginning a 40-year career in public service. A Democrat, Tingley was elected to the city commission in 1922 and served until January 1935, when he began two terms as New Mexico’s governor. In 1939, he was reelected to the city commission, where he remained until 1956. As chair of the commission, he was the informal mayor of Albuquerque. He appealed to blue-collar voters with his background in the trades, and while he lacked a college education, he had a flashy, larger-than-life appearance.

He was tenacious, crusty and loud. John Pen La Farge in a book on Santa Fe wrote, “He was Mr. Malaprop; he butchered the King’s English.” Bryan said when a newspaper criticized him for using the word “ain’t,” Tingley replied, “I ain’t agonna stop using the word ‘ain’t.’” In another anecdote, Bryan recorded that at a political rally Tingley said, “When I became your governor, I found that the Republicans had left New Mexico in a state of chaos [pronounced “chowse”]. These “Tingleyisms” abounded; even Time magazine recorded them.

Image caption: The dapper Clyde Tingley loved people and politics; as governor of New Mexico, he secured the funds for the hospital. (Photo courtesy of Sherry Fletcher, Campo Espinoso, Truth or Consequences, NM)

Image caption: The dapper Clyde Tingley loved people and politics; as governor of New Mexico, he secured the funds for the hospital. (Photo courtesy of Sherry Fletcher, Campo Espinoso, Truth or Consequences, NM)

Regardless of his lack of higher education, Tingley brought much to the state, especially through his relationship to Franklin D. Roosevelt. He first met Roosevelt in 1928, and in 1936, the president asked Tingley to join him on a political tour of Western states. The two became close friends and Tingley visited the White House some 23 times. More importantly, New Mexico benefitted from Works Project Administration (WPA) funds that Roosevelt’s New Deal provided.

One institution that was created from Tingley’s friendship with Roosevelt was a children’s hospital in New Mexico. Besides TB, another potentially fatal disease was ravishing the country: poliomyelitis. Known as polio or infantile paralysis, although not all victims were young, the disease targeted a person’s nervous system. In severe cases, victims suffered full or partial paralysis; in the most severe cases, the chest and throat became paralyzed, preventing breathing, and the person died. The first epidemic occurred in 1894 in the U.S., but it was not until 1905 that the disease was discovered to be contagious through human contact.

In 1908, the cause of polio was discovered to be a virus, but that there were three types of poliovirus was not known until 1931, and it would be 1951 before this could be demonstrated. Summer became the season for polio, and public swimming pools were closed, victims were quarantined, schools, camps and theatres closed.

In 1916, the country suffered another epidemic of polio, and in 1921, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was stricken with the virus and became permanently paralyzed from the waist down. Then he learned that a polio victim had shown improvement after swimming in the mineral waters of a resort in Georgia owned by Roosevelt’s friend, George Peabody. Roosevelt immediately tried the waters at Warm Springs and was able to stand on his own, and the muscles of his hip and shriveled leg strengthened.

Image caption: Eleanor Roosevelt, Jonas Salk (center), and Basil O'Connor (right) at The Infantile Paralysis Hall of Fame in Warm Springs, Georgia. (Photo courtesy of Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Library & Museum/ Wikimedia Commons.)

Image caption: Eleanor Roosevelt, Jonas Salk (center), and Basil O'Connor (right) at The Infantile Paralysis Hall of Fame in Warm Springs, Georgia. (Photo courtesy of Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Library & Museum/ Wikimedia Commons.)

Roosevelt bought the resort in 1926 and turned it into a famous center for treating polio patients: the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation. Roosevelt regained enough energy to serve as governor of New York and to be elected President of the United States for four terms although he lived the rest of his life in a wheel chair and died in 1945, just a few months into his last term. He rarely was photographed in the chair, however, and he pulled himself up and stood with the help of crutches and braces to further the illusion that he was not paralyzed.

Roosevelt established a home at Warm Springs, calling it the “Little White House” to make it more convenient to continue to receive treatments at the center. In the 1930s, he made polio a national concern, establishing the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (NFEP) to conduct research into the disease and to assist victims. The NFIP became the March of Dimes.

Carrie Tingley’s recovery from tuberculosis and FDR’s experience with polio encouraged the Tingleys to establish a hospital to treat children suffering from polio. New Mexico also suffered through the polio epidemics and made the couple empathetic with those who could not afford any kind of treatment. Clyde and Carrie Tingley never had children of their own but made the children who sometimes spent months and even years at the hospital their concern.

Image caption: An opened artificial respirator commonly known as the iron lung. Polio patients of the 1950s depended on these devices to breathe after being paralyzed with this devastating virus. This iron lung was donated to the CDC’s Global Health Odyssey by the family of polio patient Mr. Barton Hebert of Covington, Louisiana, who’d used the device from the late 1950s until his death in 2003. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Image caption: An opened artificial respirator commonly known as the iron lung. Polio patients of the 1950s depended on these devices to breathe after being paralyzed with this devastating virus. This iron lung was donated to the CDC’s Global Health Odyssey by the family of polio patient Mr. Barton Hebert of Covington, Louisiana, who’d used the device from the late 1950s until his death in 2003. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

During the outbreak in the 1930s, children, infants, pregnant women and the elderly developed this dreadful disease. There was no cure for polio; even today the “cure” is immunization. Children had to be kept at home in bed, away from society, because polio is a highly contagious disease. Treatment for polio in the 1930s included isolation and rest, mineral water baths in places with such natural resources, some physical therapy and placement in a contraption called the iron lung in severe cases. The first iron lung, which breathed for the patient, appeared in 1928 and an improved version, in 1931. Only the patient’s head remained outside of this tank-like machine, and the equipment was incredibly expensive.

Carrie and Clyde provided emotional support for the President when he went through polio, so they were intrigued when they found out he went to a rehabilitation center with hot springs in Georgia. Carrie was fascinated that such a place with its mineral waters could help such a horrific disease. Carrie and Roosevelt had both suffered potentially fatal diseases and had been able to find treatment because they were wealthy. However, because the Tingleys were sympathetic with the poor and the sick and they loved children, they wanted to help others in need of a place to regenerate themselves.

In searching for locations for the hospital, Carrie and Clyde found a town 150 miles south of their Albuquerque home called Hot Springs. According to another Borderlands article entitled “Hot Springs Have Long History,” the area was originally named Palomas Ojo Caliente by the Spanish, which means “Hot Springs of the Doves.” Joseph Miller in his book New Mexico: A Guide to the Colorful State wrote that the Spanish referred to the thousands of doves that once lived in the cottonwoods along the river and around the hot springs.

In 1914, the mayor changed the town’s name to “Hot Springs,” which was the name used most often. In 1949, a national radio show hosted by Ralph Edwards called “Truth or Consequences” sponsored a contest seeking a town which would change its name to Truth or Consequences. In 1950, Hot Springs changed its name to Truth or Consequences (T or C) when it won the contest.

Truth or Consequences is located near the southern Rio Grande Rift. According to Craig Martin, “tectonic forces create an extension, or stretching, of the crust. … where the crust is thinned, heat flow from the interior is high, and if water can circulate deep enough, it will be heated and rise.” The water rises through faults or cracks, flows over rocks, and spills onto the ground’s surface, where hot springs form. At Truth or Consequences, the temperature of the resulting springs is from 98 to 115 degrees. These various springs are the reason for the original name of the town.

The Warm Spring Apaches occupied this area of New Mexico and discovered the hot mineral waters that the Rio Grande Rift produced. The natives bathed in the water, believing it healed many types of injuries, especially battle wounds. The Indians were very territorial over the waters, not allowing weapons or anything negative near the water.

Many years later, people who crossed this area also felt that the water was reparative. The Riverbend Hot Springs Website explains that the water is rich in calcium, chlorides, potassium, magnesium, sodium and other minerals. These hot springs resembled the springs used in the treatment facility in Warm Springs, Ga., where President Roosevelt spent time. In Georgia, the Creek Indians and other tribes had utilized these waters many years before white men discovered them, similar to the situation in New Mexico.

During the Depression, Governor Tingley secured millions of dollars in federal funds for public projects throughout New Mexico, including University of New Mexico buildings, state fair buildings, Albuquerque’s zoo and the airport terminal, and a hospital in T or C. The WPA approved some $275,000 for construction of the hospital and two additional grants helped pay for staff quarters and the power plant.

Jack Loeffler in Survival Along the Continental Divide wrote that Bill Lumpkins, one of the hospital’s architects, did not know what should go into a hospital for polio victims. Loeffler said that Carrie Tingley picked up the phone, called FDR’s wife Eleanor Roosevelt, who in turn called the architect in Warm Springs. He flew to New Mexico and guided Lumpkins and Frank Stoddard in building the hospital along the lines of the Warm Springs facility.

The Sierra County, N. M. Website entitled Campo Espinoso stated that many other concerned citizens were pushing for this hospital to be opened. They had the support from President Roosevelt, who was working on the national front to seek treatments for children with polio as soon as possible. To honor the governor’s wife for her compassion for children, the sick and the poor, the hospital was named for her.

Image caption: Hydrotherapy at the Tingley Hospital. (Photo courtesy of Sherry Fletcher, Campo Espinoso, Truth or Consequences, NM)

Image caption: Hydrotherapy at the Tingley Hospital. (Photo courtesy of Sherry Fletcher, Campo Espinoso, Truth or Consequences, NM)

On Saturday, May 29, 1937, the Carrie Tingley Hospital for Crippled Children opened to the public. The hospital was beautifully built on 118 acres of land and the building included steel beams and a concrete roof, ready for the second story. Built in Territorial Revival style, the exterior of white stucco featured attractive tall columns. The nurses and staff stayed on the second floor of the hospital. The hospital had approximately 100 beds and served children from birth to 21 years.

The primary focus of the hospital when it opened was to help children with polio, but it also treated other orthopedic problems. Most of its first patients were children with polio from Indian reservations. In 1937, the hospital provided hot mineral baths as part of their treatments which helped many children work the muscles in their limbs and the rest of their bodies. Patients with severe cases were placed in iron lungs. Surgery, physical therapy, braces and corrective shoes also were used to treat patients. According to the Campo Espinoso, the treatments depended on how serious the virus was. The staff also took advantage of the climate — the hot dry air the children enjoyed.

The website also said that the hospital had two very important therapies, heliotherapy and hydrotherapy. When performing heliotherapy, the nurses would wheel chairs and beds (they were on wheels) to place the children in the courtyard and allow the sun to shine on them. Hydrotherapy consisted of putting children in the mineral water to soak. Devices called Hubbard Tubs held several children at a time. Sometimes the patients were so sick that they would have to stay at the hospital for weeks or even months. Their parents had to leave them there and return to work or home. As Tingley had promised, the hospital did not discriminate by race, religion or ability to pay.

Suzanne Stamatov stated that Carrie Tingley worked for the hospital mostly behind the scenes. She visited the children often and raised money for the children’s surgeries and medicines. Carrie advised these children to continue their lives as normally as possible. She did not want them to think of themselves as having a disability.

According to the New Mexico Office of the State Historian, the Tingleys had built huge shelves in their Albuquerque home at 1524 Silver SE to hold the hundreds of toys they collected all year long for the holidays. On Christmas, every child at Carrie Tingley received gifts, dolls for the girls, airplanes or trucks for the boys, given out by Santa Claus. Some children preferred to stay at the hospital for Christmas because they received more gifts there than they would at home! According to the Albuquerque Journal, Carrie always made sure that the young patients focused on their education. She also made sure that they had a good pair of shoes.

Image caption: Turtleback Mountain, T or C. Photo courtesy of Sherry Fletcher, Campo Espinoso, Truth or Consequences, NM)

The children at the hospital were surrounded not only with the natural beauty of the springs and Turtleback Mountain in the background, but also with art produced through the WPA’s federal art project. According to Charles Bennett, Eugenie Shonnard created the “Turtle Pond,” a lovely terra cotta fountain in the hospital’s inner courtyard which featured four sculpted frogs on the top tier, four ducks on the second tier, with the animals streaming water, and four turtles on the bottom tier facing the four directions.

Related to the turtle pond and Turtleback Mountain overlooking the hospital building is the fact that one of the hospital’s renowned orthopedic patients was New Mexican author Rudolfo Anaya, who wrote Bless Me, Ultima. He also wrote a novel entitled Tortuga (Spanish for turtle), a narrative by a young man in a body cast, ostensibly based on Anaya’s own experiences as a youth at Carrie Tingley Hospital.

Cisella Loeffler created two large paintings at the hospital reflecting New Mexico’s Indian, Hispanic and Anglo cultures done in child-like figures, including a nativity scene, according to Kathryn A. Flynn in her book The New Deal: a 75thAnniversary Celebration.

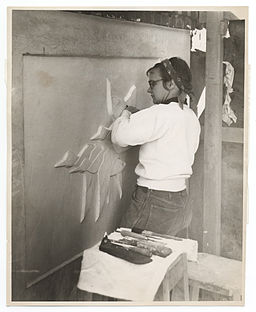

Image caption: Irene Emery at work on carving on the wall of the sun room at Carrie Tingley Crippled Children's Hospital, Hot Springs, New Mexico circa 1937. (Photo courtesy of Archives of American Art/ Wikimedia Commons)

Image caption: Irene Emery at work on carving on the wall of the sun room at Carrie Tingley Crippled Children's Hospital, Hot Springs, New Mexico circa 1937. (Photo courtesy of Archives of American Art/ Wikimedia Commons)

Another artist who benefitted from New Deal programs to provide public art was Oliver LaGrone, the first African-American to graduate from the University of New Mexico Art Department. He depicted a mother gently holding a young boy in front of her to memorialize his own mother nursing him through malaria. Children often climbed on the life-size sculpture entitled “Mercy.” Jason Silverman in Untold New Mexico: Stories from a Hidden Past wrote that the sculpture was moved to Albuquerque when the hospital moved, and the mother’s missing thumb, worn down over the decades from being touched, was replaced by the artist.

The staff treated the children as if they were their own, and the hospital was fairly self-sufficient. In an interview filmed by Campo Espinoso for New Mexico’s Centennial in 2012, Daisy Wilson, a nurse who worked at Carrie Tingley Hospital, said the hospital “treat[ed] the whole child.” Children attended school in grades K-12, taught onsite. Every attempt was made to keep the children busy so they did not have time to obsess about their condition. Area farmers provided fresh vegetables and ranchers provided beef, mutton and lamb. Even the braces some children needed were made onsite.

In the 1950s, a vaccination for polio was developed, the inactivated polio vaccine by Dr. Jonas Salk, and then the oral polio vaccine was developed in the 1960s by Dr. Albert Sabin. Fear of the disease began to subside along with the number of polio cases. The Carrie Tingley Hospital began to focus on other orthopedic problems of children such as cerebral palsy, scoliosis, clubfoot and others.

Image caption: Carrie Tingley Hospital on the University of New Mexico campus. (Photo courtesy of Perry Planet/Wikimedia Commons.)

Image caption: Carrie Tingley Hospital on the University of New Mexico campus. (Photo courtesy of Perry Planet/Wikimedia Commons.)

Carrie Tingley Hospital moved to Albuquerque in 1981 because it was closer to other medical facilities and was easier for doctors and consultants to access. Its purpose was no longer the treatment of polio, which was eliminated from the US in 1979, but all pediatric orthopedic conditions. It is now a division of the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center. It still accepts patients from birth to 21-years-old and is the only rehabilitation hospital for children in New Mexico. The hospital created the Carrie Tingley Hospital Foundation to raise money for surgeries and equipment to help families of patients.

go to top

The Tingley Hospital was only one of an estimated 4,000 projects funded in New Mexico as part of the WPA program, many related to education. According to Howard Bryan, Tingley opened a series of ponds for swimming in the 1930s called Tingley Beach on the Southwest side of Albuquerque, so large it had eight lifeguards and was a popular picnic spot. Swimming is no longer allowed, but Tingley Beach has been renovated and now is known for its fishing and pedal boats.

Tingley Beach is part of the ABQ BioPark, which also includes what was once Tingley Field, the baseball stadium which hosted the Albuquerque Dons, later renamed the Dukes. The field is now part of the zoo grounds. The BioPark also includes the aquarium and botanic garden. Tingley Coliseum, part of the state fairgrounds, is used for musical and sports events and was once home to the Albuquerque hockey team. Clyde and Carrie Tingley are honored with near life-size bronzes in the BioPark for their philanthropy and efforts at beautifying early Albuquerque and providing recreational opportunities.

Image caption: Bronzes of Carrie and Clyde Tingley and a child greet visitors to Tingley Beach in Albuquerque, N.M. (Photo by Naomi Iniguez).

Image caption: Bronzes of Carrie and Clyde Tingley and a child greet visitors to Tingley Beach in Albuquerque, N.M. (Photo by Naomi Iniguez).

Clyde Tingley often visited the children’s hospital named for his wife. In 1937, he even had the entire New Mexico legislature drive down to Hot Springs to tour the hospital. He established a political machine in the state and governed with an iron hand. But regardless of his politics, he was a compassionate man and carried about the poor, the hungry and those out of work, and he tried to solve the problems the Depression caused.

Tingley loved red chile, and his wife, who called him “Buster,” carried Tums in her purse just in case he needed them. He died on Christmas Eve 1960 in Albuquerque. He was a tenacious man, often flamboyant in public, known for wearing his linen suits and the famous 1890s hat, the fedora. He loved schmoozing with celebrities and would often meet the train in Albuquerque when he knew movie stars were on it. But he enjoyed talking with all types. He was a true “people” person.

Carrie Tingley went about her philanthropic activities without much ado. She held little truck with elaborate entertaining in the Governor’s mansion in Santa Fe, and social classes meant little to her. However, she was a very animated and outgoing person who enjoyed collecting antiques, the color lavender and going to the movies weekly. She had big, beautiful red hair and loved wearing huge, colorful hats. She died at her home in Albuquerque on Nov. 6, 1961, less than a year after her husband. According to Richard Melzer, she was 84 and had suffered from leukemia and a stroke. Carrie and Clyde Tingley are buried at the Fairview Cemetery in Albuquerque. Melzer noted that the Tingleys left the hospital and other charities a large amount of money in their will.

The original hospital building in T or C was later turned into the New Mexico State Veterans’ Home. The residents still use the mineral waters. The exterior of the building looks almost the same as it did when it housed the hospital, so well-built it was. The town of T or C also offers many opportunities for its residents and visitors to use the healing mineral waters.

Carrie and Clyde Tingley ended up in New Mexico by chance, but she was transformed by her illness and the couple used their influence, energy and money to change many lives. It is a tribute to this passionate couple that the children’s hospital in Albuquerque kept the name Carrie Tingley.

Tags: biography

Going the Extra Yard: An Army Doctor's Odyssey

by

Going the Extra Yard: An Army Doctor's Odyssey

by